Live like a sprinter!

Sarah McGill | Articles

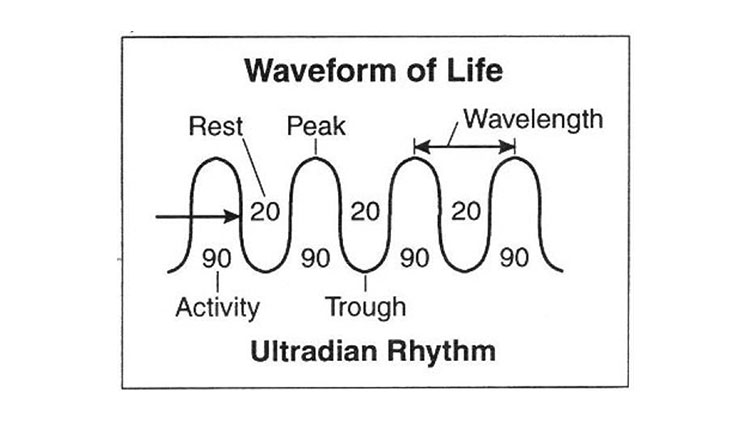

In his article “The 90 minute solution: live like a sprinter” Schwartz introduces sleep researcher, Nathaniel Kleitman. Kleitman’s observations are of the “basic rest-activity cycle”: the 90 minute periods at night during which we move progressively through five stages of sleep, from light to deep, and then out again. Now, according to Kleitman, our bodies operate by the same 90 minute rhythm during the day. When we’re awake, we move from higher to lower alertness every 90 minutes. Other researchers have called this our “ultradian rhythm” (see graph).

In his article “The 90 minute solution: live like a sprinter” Schwartz introduces sleep researcher, Nathaniel Kleitman. Kleitman’s observations are of the “basic rest-activity cycle”: the 90 minute periods at night during which we move progressively through five stages of sleep, from light to deep, and then out again. Now, according to Kleitman, our bodies operate by the same 90 minute rhythm during the day. When we’re awake, we move from higher to lower alertness every 90 minutes. Other researchers have called this our “ultradian rhythm” (see graph).

So apply this to any human activity, as many groups of people have done. For example, an athlete will train hard for up to but no more than 90 minutes. He will then take a break for an extended amount of time before going back to training. The results have proven to be fantastic – athletes are able to run faster, lift more, etc. by adopting this approach. Schwartz reports on other groups of people – musicians, writers and chess players – have also tested this method and I’m sure you can guess the result. Each group obtained extraordinary results. They were able to perform better / write more by breaking their practice time into small chunks of up to 90 minutes at a time.

As Schwartz explains, “Our bodies sends us clear signals when we need a break, including fidgetiness, hunger, drowsiness and loss of focus. But mostly, we override them. Instead, we find artificial ways to pump up our energy: caffeine, foods high in sugar and simple carbohydrates, and our body’s own stress hormones — adrenalin, noradrenalin and cortisol. After working at high intensity for more than 90 minutes, we begin to draw on these emergency reserves to keep us going. In the process, we move from parasympathetic to a sympathetic arousal — a physiological state more commonly known as “fight or flight.””

Think about it. We all experience this on a daily basis – and many of us regularly throughout the day. While it may not be realistic to work for 90 minutes at a time and then take a 20 minute break, I’d be willing to bet that you have the flexibility to adopt a variation of this methodology. Case in point: I recently had some “thinking” work that had to be done in the middle of a busy day filled with calls, meetings and other ‘to-dos’. I was finding it impossible to concentrate on the subject at hand, and turn my mind to a completely different job (that couldn’t be ticked off promptly). I went outside the office and took a brisk 5 minute walk around the block. When I came back, I was not only able to focus on starting the “thinking” but also completed the task in good time. And, I was proud of the results.

Challenge yourself to take at least one break throughout the day to “do nothing” (no talking, etc. during this time). Throw something physical movement in – a walk, jump, run, a wander (which gets blood pumping and energizing hormones flowing). Then follow-up this time with a particularly difficult task, or at least one that requires your complete focus. If you are a manager, lead by example and encourage your people to do the same – you will be amazed at the results.

Good Luck!